|

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

Zeiss Ikon history

For some, Zeiss Ikon has no meaning. It's just some variation of the Carl Zeiss name. But in fact, Zeiss Ikon is much more than that. It is one of the most important names in the history of photography.

This story of Zeiss Ikon dates back to 1926 with the merger of four of Germany's biggest camera makers: Contessa-Nettel, of Stuttgart; Ernemann Werke, of Dresden; Goerz, of Berlin; and Ica, of Dresden, which themselves (except for Goerz) had been formed or had expanded through mergers. Zeiss Ikon's relationship to Carl Zeiss, the parent firm, is that Zeiss Ikon was seen in many ways as just another customer for its highly regarded lenses.

At

the time of the merger, the folding roll-film camera was beginning to replace

the plate- and sheet-film camera in the amateur market. The quality of roll

film was very good, and the convenience of folding the camera and slipping

it into a pocket combined with the ability to shoot between eight and 16

shots per roll certainly played a role in its rising popularity.

At

the time of the merger, the folding roll-film camera was beginning to replace

the plate- and sheet-film camera in the amateur market. The quality of roll

film was very good, and the convenience of folding the camera and slipping

it into a pocket combined with the ability to shoot between eight and 16

shots per roll certainly played a role in its rising popularity.

A photographer was no longer limited by the number of film holders he or she could carry. Now, it was possible to carry six spools of 120 film and shoot as many as 96 photos with a 6cm x 4.5cm camera or 48 shots with a 6x9 camera – without any fuss or back-breaking labor. Because many sheet-film holders weren't reversible, a photographer would have to carry 48 heavy steel holders, which often meant a large wooden case and tripod coupled with a strong back or an assistant.

Many of Zeiss Ikon's first cameras, however, were the same plate- and sheet-film cameras from the pre-merger companies. But it wasn't long before some of Zeiss Ikon's own folding roll-film cameras began to make their way onto the market. In addition to the pre-merger Tenax, Bob and Cocarettes, there also was the Nettar, Ikonta and Super Ikonta. It took a number of years until the plate cameras disappeared from the Zeiss Ikon catalog, and in fact several of them survived into the late 1930s. There simply were too many models and variations within each model to attempt to list them here. But no plate- or sheet-film camera was produced by Zeiss Ikon after World War II.

The importance of the Leica camera and Kodak's role in all of this

The year before Zeiss Ikon was formed, another equally important development occurred in Wetzlar, Germany, that would move photography in yet another direction and one that would have lasting effects to this day. It was the public introduction of the Leica in 1925 and the so-called miniature 35mm format – the culmination of an idea that Oskar Barnack had been working on for nearly two decades. All at once, the Leica camera created an entirely new segment of photography.

While the earliest Leicas posed their own challenges to users: no rangefinder

and required photographer to spool their own film, the ability to shoot

36 frames per roll certainly was enticing. The small camera allowed the

photographer to be unobtrusive, and with the collapsible Elmar, he could

pull the camera from the pocket of his jacket, snap a photo or two or even

three – taking

advantage

of the quiet cloth focal-plane shutter – then collapse the lens, put the

camera back into his pocket and be on his way.

advantage

of the quiet cloth focal-plane shutter – then collapse the lens, put the

camera back into his pocket and be on his way.

The Leica also spawned two Kodak products in 1934 that would popularize 35mm photography in a way that few could have expected. Kodak introduced the Retina and the standard daylight-loading 35mm cartridge that is for all intents and purposes the same one that we use today. The diminutive folding Retina came from Kodak's new German operation: Kodak AG, formerly Nagel Camera Werks, which was owned by Dr. August Nagel, a former Zeiss Ikon camera designer and formerly of Drexler & Nagel – a predecessor firm to Contessa-Nettel that was part of the merger that formed Zeiss Ikon.

As mentioned before, Leica photographers had to cut, spool and load their own 35mm film – in total darkness. Kodak replaced all of that with one easy product and brought 35mm out of the darkness, so to speak, and into the hands of the common man or woman. With this simple cartridge and a small, affordable camera, Kodak introduced 35mm photography to the masses.

It

took Zeiss Ikon six years to market its competitor – the Contax. The first

Contax was big, boxy and rather clunky, compared with the svelte Leica.

The one thing the Contax had going for it was the excellent Carl Zeiss lenses.

The Contax II was introduced in 1936 with a new body design and a number

of improvements, including some that bested the Leica. The Olympia 18cm

Sonnar was offered in time for the 1936 Olympics (more

about the Contax).

It

took Zeiss Ikon six years to market its competitor – the Contax. The first

Contax was big, boxy and rather clunky, compared with the svelte Leica.

The one thing the Contax had going for it was the excellent Carl Zeiss lenses.

The Contax II was introduced in 1936 with a new body design and a number

of improvements, including some that bested the Leica. The Olympia 18cm

Sonnar was offered in time for the 1936 Olympics (more

about the Contax).

Zeiss Ikon continued to offer numerous folding, box and twin-lens cameras in different formats, although it avoided Kodak's 620 format. Photographers could always use 620 film in its 120 cameras, but Zeiss Ikon never made any cameras specifically for that format. (A small note: The first Ikoflex twin-lens reflex had dual film counters – one for 120 and another for 620, so I suppose you could argue that Zeiss Ikon accommodated 620 in one of its cameras.)

The Nettars served the lower end of the roll-film market, and the Ikonta and Super Ikonta were priced higher for the well-heeled amateur or professional. Zeiss Ikon's product for the point-and-shoot photographer was the Box-Tengor, a holdover from Goerz, which featured the ever popular Goerz Frontar meniscus lens and was available in 127, 6x4.5 and 6x9 formats. The Baby Box Tengor, using 127 film, also had a focusing Novar – the only Box Tengor in any format that offered the buyer a choice of two lenses. Two other Zeiss Ikon cameras for the 127 format were the Kolibri, which was one of the few 127 cameras with a spring-loaded collapsible Novar or Tessar, and the Ikonette and its Frontar lens.

At the same time, Zeiss Ikon used the Contax II as the basis for three other 35mm cameras: Super Nettel, Nettax and the Contaflex. Meanwhile, the popularity of the motor-driven Robot and the square format drove Zeiss Ikon to answer with two of its own 24mm x 24mm products: Tenax II and Tenax I. Curiously, the Tenax II arrived before the Tenax I.

Zeiss

Ikon rarely allowed competitors to have a market to itself. The mighty Ikoflex

was Zeiss Ikon's answer to the Rolleicord and Rolleiflex twin-lens cameras.

The first Ikoflex had a Novar lens while successive models offered either

a Carl Zeiss Jena Triotar or Tessar.

Zeiss

Ikon rarely allowed competitors to have a market to itself. The mighty Ikoflex

was Zeiss Ikon's answer to the Rolleicord and Rolleiflex twin-lens cameras.

The first Ikoflex had a Novar lens while successive models offered either

a Carl Zeiss Jena Triotar or Tessar.

In 1935, Zeiss Ikon brought forth the most advanced – and one of the heaviest cameras – of the day: the Contaflex twin-lens reflex that used 35mm film. The camera boasted the first built-in selenium light meter, interchangeable lenses, a focal plane Contax-style shutter and a van Albada sports viewfinder. The lenses were the same as those offered for the Contax II but in a Contaflex mount. The camera cost a small fortune then and today.

Production at Zeiss Ikon slowed to a crawl during World War II, and the bombing of Dresden caused severe damage to Zeiss Ikon's factory, including the loss of blueprints and prototypes of many Zeiss Ikon cameras, including the Contax. Further, the division of Germany into East and West zones and the division of Carl Zeiss into competing operations in both zones further complicated the future of Zeiss Ikon.

After World War II

When World War II ended, much of Germany was in shambles, and Zeiss Ikon

had been particularly hard hit. Much retooling needed to be done, and it

took a full five years until the Contax name reappeared -- now as the Contax

IIa. The new camera revived the Contax lens mount, but it otherwise was

a completely new camera, sharing no parts with the Contax II.

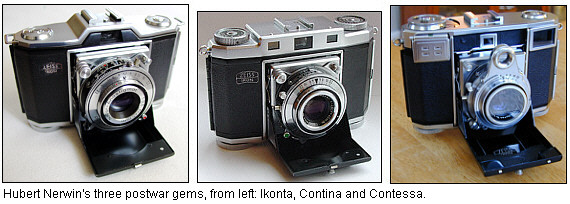

Meanwhile, Zeiss Ikon continued to serve other markets, both professional and amateur. The Ikoflex twin-lens cameras returned, and Zeiss Ikon designer Hubert Nerwin created three small folding 35mm cameras – among the most perfect cameras ever made: the Ikonta 35, Contina and Contessa. The three roll-film (6x4.6, 6x6 and 6x9) Ikontas and Super Ikontas resurfaced, as did the lower-priced Nettar and a medium format Nettax (not to be confused with the 35mm rangefinder camera of the same name).

As the market moved forward, folding cameras fell out of favor. The folding Ikonta, Contina and Contessa were replaced with rigid-lens models, and production of the Nettar, Nettax, Ikonta and Super Ikonta ended. Zeiss Ikon also offered its plastic Ikonette – a stylish gray-bodied camera with a coated Novar lens. It suffered from light leaks and was recalled.

Zeiss Ikon never further developed the Contax as the market began to shift toward the single-lens reflex camera, and the Contax was dropped in the early 1960s.

Of course, Zeiss Ikon also had cameras for the growing SLR segment: the Contaflex (a different camera from the Contaflex TLR) for the amateur photographer, and the Contarex for the professional photographer, as well as those who could afford it.

The Contarex was big and heavy and featured the best Carl Zeiss lenses of the day. They continue to be some of the best lenses available, and you'd be hard pressed to be disappointed with the quality of the images they produce. For the most part, the Contaflex relied on Tessar lenses, although some models offered a Pantar lens. Still others featured interchangeable front elements.

Later, after absorbing Voigtlander, Zeiss Ikon produced the Icarex series that featured either a 42mm thread or bayonet mount and focal-plane shutter. Some models were branded Zeiss Ikon, while others were branded Zeiss Ikon | Voigtlander. This camera became the basis for the Rolleiflex SL35 series.

By the late 1960s, Zeiss Ikon could no longer compete with the huge influx of cheaper Japanese cameras from companies that seemed quicker to innovate. And price, rather than ultimate quality, now drove the mass market. The new Nikons, Canons, Pentaxes, Minoltas and Olympuses proved to be very good cameras with excellent lenses. Yashica and several others served the lower-priced market segment.

Zeiss Ikon folded in 1972, and one of the greatest camera companies that the world had known passed into history. For those of us who continue to buy, restore and use the Zeiss Ikon cameras, the return of the Zeiss Ikon name is more than marketing. It pays homage to one of photography's historic names. To understand the present and future, it helps to have an appreciation, awareness and understanding of the past.

Important note

The story of Zeiss Ikon is much longer and more complicated and involves Voigtlander, Rollei, the Soviet Union and many other factors. I could never hope to do justice to it in a single Web page. It is covered quite thoroughly in two books:

- "Zeiss Ikon Cameras," by D.B. Tubbs

- "Zeiss Compendium East and West – 1940-1972," by Marc James Small and Charles Barringer

If you want to know more about buying and using Zeiss Ikon cameras, visit the Links page or join some of the discussion boards that deal with classic cameras. I also maintain another area that lists a small number of classic cameras. One small warning: It can be highly addictive.